Servo, Stepper, or DC: When Each Motor Type Makes Sense

Confused by servo, stepper, or DC motors? Learn how each works, trade-offs in cost, precision, speed, and control, and when to pick the right one.

Choosing the Right Motor: Selecting between DC, stepper, and servo motors starts with clarifying motion goals, not just shopping parts. Define the required torque, speed range, and position accuracy, then map those to control complexity, power budget, and cost. For simple spinning tasks with broad tolerances, a DC motor is often the most direct path. For discrete, repeatable positioning without sensors, a stepper motor shines. When you need fast, precise motion under changing loads, a servo motor leads. Consider the full system: driver electronics, feedback, gearing, inertia, and duty cycle. A motor that looks perfect at no load can stumble under acceleration or stall when heat builds. Think about start-stop frequency, run time, environment, and maintenance. Many strong designs mix types, such as steppers for low-cost axes and servos for the high-performance axis. Framing the decision this way helps you avoid oversizing, underpowering, or overcomplicating what could be an elegant solution.

When DC Motors Shine: A DC motor is the champion of simplicity, continuous rotation, and value. With basic PWM speed control and a modest driver, it can drive fans, pumps, conveyor rollers, and wheels reliably. The torque-speed curve is predictable, and adding a gearbox yields useful stall torque and lower output speed for practical loads. DC motors excel when you need smooth motion, soft starts, and steady-state performance without strict position targets. For better regulation, pair a DC motor with a tachometer or encoder to stabilize speed under load; add a PID loop for improved control. If you require precise positioning, recognize that a DC motor with feedback and a proper controller effectively becomes a servo arrangement, with added cost and complexity. Limitations include weak open-loop positioning, potential overshoot without tuning, and brush wear in brushed variants. Still, for battery-powered devices, budget builds, or long, uncomplicated runtimes, DC remains a dependable, efficient workhorse.

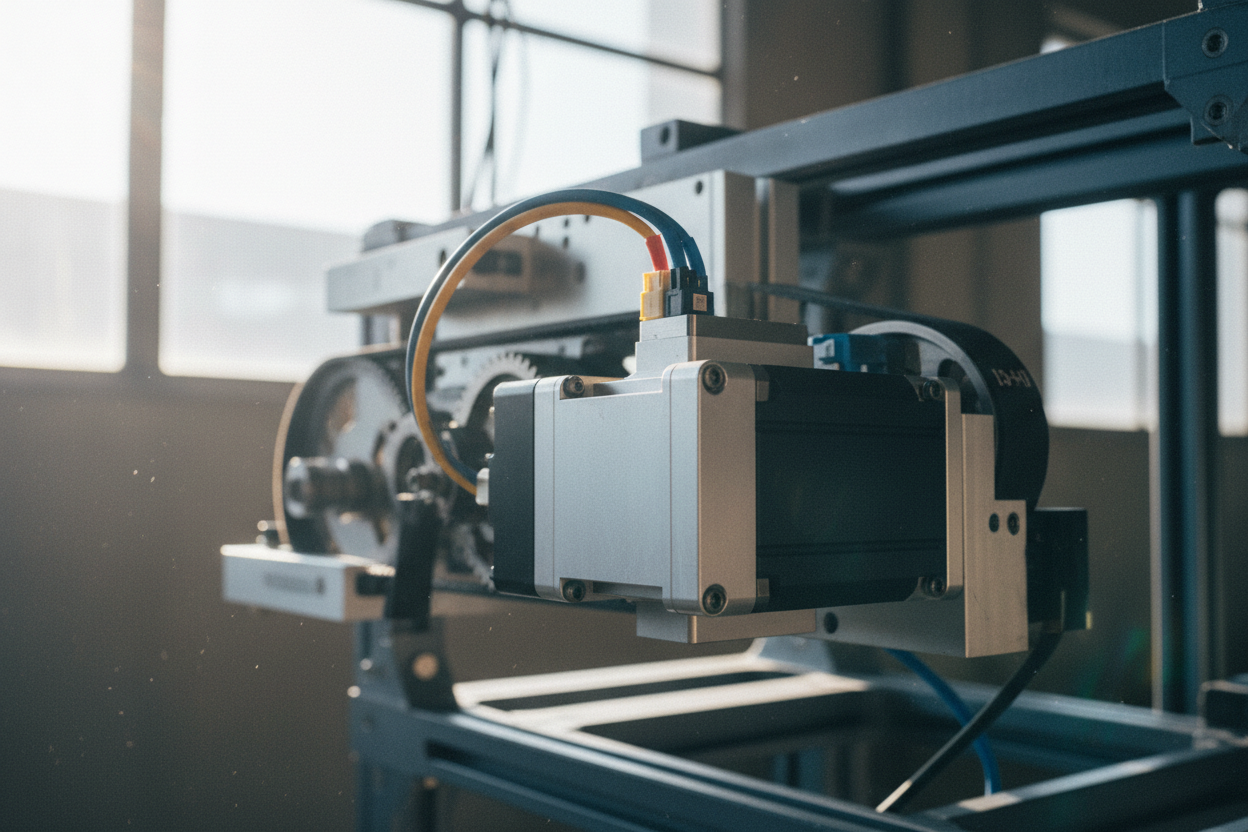

When Stepper Motors Are Ideal: A stepper motor offers open-loop positioning by moving in discrete steps, delivering excellent holding torque and repeatability without mandatory feedback. This makes steppers popular in 3D printers, light CNC motion, lab automation, and indexing mechanisms. With a capable driver, microstepping smooths motion and reduces vibration while increasing effective resolution, though actual torque per microstep is lower. Be aware of resonance zones, where mechanical and electrical dynamics can cause roughness or missed steps; careful acceleration ramps, damping, or different drive modes help. Steppers provide strong low-speed torque but lose torque as speed rises, and they can lose steps if overloaded, since open-loop control assumes commanded motion is achieved. For moderate speeds, predictable loads, and cost-sensitive builds, steppers balance precision, simplicity, and availability. Add an index or home sensor for recovery and confidence, or layer on an encoder for hybrid closed-loop performance when applications demand extra margin against stalls.

When Servo Motors Lead: A servo motor system marries a motor with closed-loop feedback, typically via an encoder or resolver, and a tuned controller. The result is high dynamic response, strong torque at speed, and excellent position and velocity control under varying loads. Servos shine in robotics, coordinated multi-axis machinery, and heavy or fast CNC motion where bandwidth, stiffness, and accuracy matter. Expect richer commissioning: PID gains, feedforward, and inertia matching influence performance and stability. You also get helpful diagnostics like following error and real-time current data. Servos handle aggressive motion profiles and recover gracefully from disturbances, maintaining commanded trajectories. They cost more and require more sophisticated drivers and wiring, yet they lower risk when failure or drift is unacceptable. If your system demands rapid indexing, tight settling times, smooth contouring, or torque control for pressing and winding, a well-chosen servo architecture is the most capable, scalable option.

Control, Power, and Integration Tradeoffs: Motor choice is inseparable from the drive electronics, power supply, and controller. DC drives are light on features but easy to integrate; stepper drivers handle current limiting, microstepping, and resonance ranges; servo drives manage feedback, loop closure, and fault handling. Plan for peak current versus continuous current, wire sizing, EMI mitigation, and grounding. Understand back-EMF, regenerative energy, and whether you need a braking resistor or energy return strategy. Budget for homing, limit switches, and safety interlocks such as e-stops. Real-time control matters: tight synchronization and S-curve profiles improve reliability and reduce oscillation. On the software side, abstract motion commands from hardware so you can upgrade from stepper to servo later if requirements grow. Good integration treats the motor, driver, mechanics, and control code as a unified system, preventing surprises like mid-profile stalls, brownouts, or oscillations.

Environment, Duty Cycle, and Reliability: Your operating context shapes motor success. Consider duty cycle, ambient temperature, and thermal management; steppers waste heat at standstill, DC motors can run cool when lightly loaded, and servos manage heat actively but may need airflow or heatsinking. Exposure to dust, humidity, or chemicals favors sealed components and robust connectors. Vibration and shock call for rigid mounting, balanced couplings, and careful inertia ratios. Maintenance differs: brushed DC requires brush and commutator care, while stepper bearings and couplings need inspection; servo systems may include thermal and current diagnostics to predict issues. Consider efficiency for battery-powered platforms; servos often deliver better performance-per-watt under dynamic loads, while steppers can be less efficient at high holding torque. Noise sensitivity steers choices as well; microstepped steppers and well-tuned servos can be quiet. Planning for lifecycle, spares, and serviceability beats late-stage redesigns every time.

A Practical Selection Playbook: Align the motor to the job. Choose DC when you need low-cost, variable-speed continuous rotation with modest control effort, like pumps, fans, or wheels where position accuracy is secondary. Choose a stepper for repeatable positioning with predictable loads, moderate speeds, and budget-friendly electronics, such as light CNC, dispensers, and indexing tables. Choose a servo for demanding precision, changing loads, high speed, or when missed moves are unacceptable, such as robotics, packaging axes, and coordinated motion. Validate assumptions with a quick load calculation and a prototype that measures current, temperature, and position error. Add sensors for homing and safety margins to avoid stalls or drift. Do not hesitate to mix types: a servo on the critical axis, steppers for auxiliaries, and DC for drives or feed systems. Make space for future upgrades, and you will scale performance without ripping out your architecture.