Sizing a Motor: Calculating Torque, Load, and Duty Cycle

Learn how to size a motor by calculating torque from load and motion profiles, accounting for inertia, gear ratios, duty cycle, and thermal limits.

Understanding Torque and Load

Sizing a motor starts with a clear definition of the load and the motion you need. Torque is the twisting effort that overcomes resistance and causes rotation, defined as force times radius. In real applications, total load torque blends several components: static torque to hold position, frictional torque from bearings and seals, gravitational torque for lifting, and process torque for cutting, mixing, or pumping. Map the motion profile first: target speed, required acceleration, positioning accuracy, and any dwell periods. Note constraints like available supply voltage, space, ambient conditions, and permissible noise or vibration. Establish units early (for example, newton meters and radians per second) to avoid conversion errors. Then separate what is constant from what is dynamic: constant torque to run at speed versus transient torque to start and accelerate. This distinction forms the backbone of a reliable sizing process for motors, guiding choices on motor type, drive, gearing, and the thermal headroom needed to handle peaks without overheating.

Breaking Down the Torque Equation

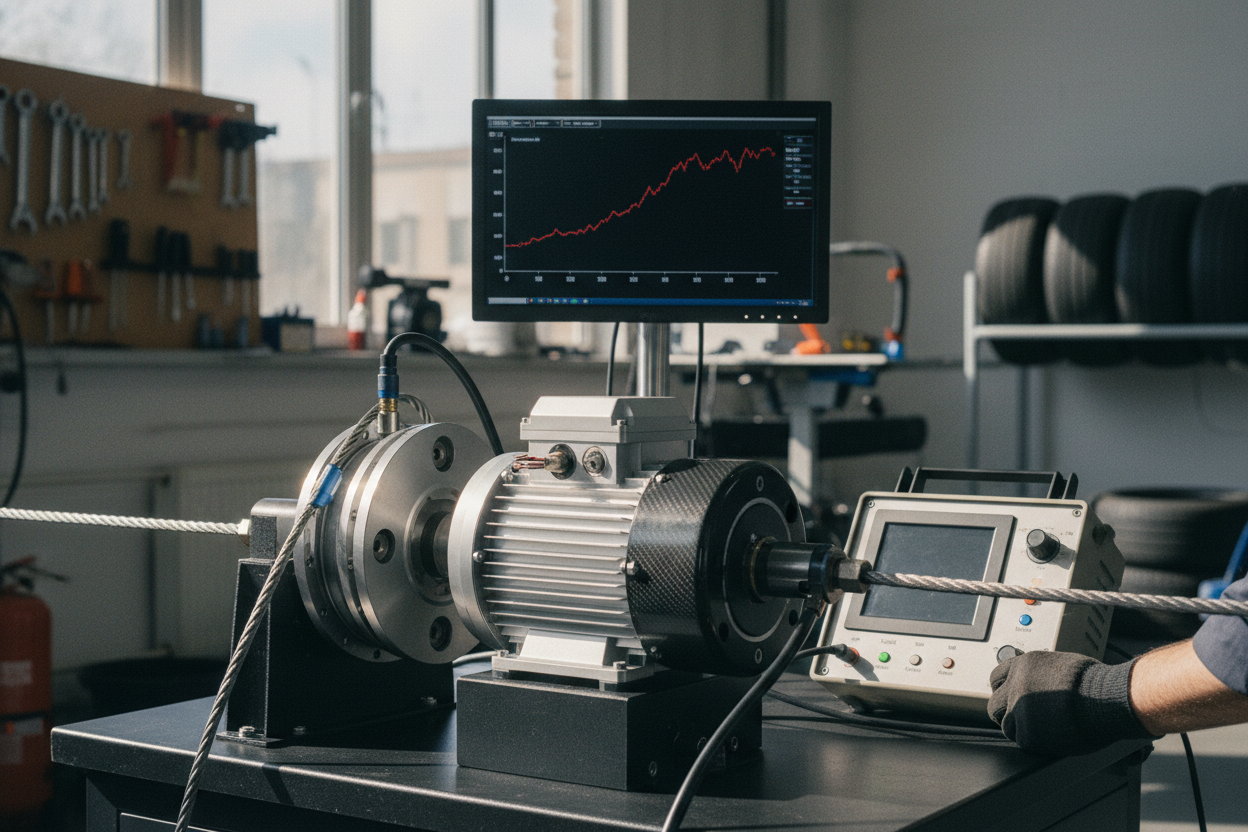

To compute required torque, sum resistive torques and add the torque to accelerate inertia. A practical relationship is: T_required = T_load + T_friction + J_total × alpha, where J_total is the combined inertia reflected to the motor shaft and alpha is angular acceleration. Include the motor's own rotor inertia, couplings, and any reflected inertia from gearboxes or mechanisms. Estimate friction conservatively; bearings, seals, and guides contribute more than expected under poor lubrication or misalignment. Convert speeds to radians per second and accelerations accordingly. For example, accelerating a moderate inertia quickly can demand several times the steady running torque, even before accounting for process torque. Add a safety factor to cover tolerances, wear, and temperature effects. Check the speed-torque curve of candidate motors: the available torque falls as speed rises due to back EMF and drive limits. Ensuring the curve stays above your calculated requirement across the motion profile is essential to robust operation.

Duty Cycle and Thermal Reality

Motors are thermal machines, so the duty cycle determines how much continuous and peak torque they can safely deliver. Define the cycle: durations of acceleration, constant speed, deceleration, and rest. Compute RMS torque to represent the thermal load: T_RMS = sqrt(sum(T_i^2 × t_i) / sum(t_i)). Compare T_RMS to the motor's continuous torque rating; compare the highest segment torque and duration to the peak torque capability and allowable time. Short bursts above continuous torque are acceptable if the motor's thermal mass absorbs the heat and the average stays within limits. Consider the environment: restricted airflow or higher ambient temperatures reduce allowable continuous torque. Verify cooling provisions, from natural convection to forced air or conduction to the machine frame. If T_RMS is close to the limit, choose a motor with more thermal margin or modify the motion profile to reduce peaks. Proper duty analysis prevents nuisance trips, drift in accuracy, and premature insulation aging.

Speed, Gearing, and Reflected Inertia

Gearing reshapes the problem by trading speed for torque and modifying reflected inertia. With a gear ratio GR (motor turns per load turn), approximate relationships are: T_load ≈ T_motor × GR × eta and speed_load ≈ speed_motor ÷ GR, where eta is the gearbox efficiency. Importantly, reflected inertia to the motor is J_ref = J_load ÷ GR^2, which can dramatically reduce acceleration torque when GR is chosen well. Balance this with mechanical limits, backlash, compliance, and gearbox heating. Higher GR boosts torque but caps load speed, and losses grow as eta drops under load and misalignment. Plot your speed-torque requirement after gearing and overlay gearbox limits for input speed and allowable torque. If the application needs fast reversals or precision positioning, prioritize low backlash and adequate torsional stiffness. Use the smallest GR that meets torque while keeping motor speed comfortably below electrical and mechanical limits. The right gearbox can shrink motor size, smooth control, and increase overall system efficiency.

Choosing the Right Motor Technology

Different motor technologies suit different torque, speed, and control demands. Brushed DC motors offer simple control and strong low-speed torque, with brushes that wear and create electrical noise. Brushless DC (BLDC) and PMSM motors deliver high efficiency, smooth torque, and excellent power density, requiring an electronic drive for commutation and precise control. Steppers provide open-loop positioning with high holding torque at low speeds, but torque drops with speed and resonance must be managed; closed-loop steppers mitigate these limits. AC induction motors excel in robustness and constant-speed loads, and with variable frequency drives they handle moderate dynamic profiles well. Servo systems, typically BLDC or PMSM with feedback, are ideal for rapid accelerations, tight position or velocity loops, and varying duty cycles. Match the motor's torque constant, inertia, and thermal rating to the application, and ensure the chosen drive supports current, voltage, feedback devices, and motion features like field weakening, jerk limits, and anti-resonance tuning.

Power, Current, and Drive Matching

Tie mechanical needs to electrical capability via P = T × omega. This power must flow through the drive, the supply, and the motor's windings with acceptable current and voltage margins. Check the motor's torque constant (Kt) to link torque and current, and the speed constant (Kv or back EMF) to relate speed and voltage. Ensure the drive can supply the required peak current for acceleration without exceeding motor thermal limits, and that the continuous current rating clears your RMS demand. Consider regenerative energy during deceleration; the drive must dissipate or return it to the supply safely, sometimes with a braking resistor. Confirm wiring gauge, insulation class, and expected temperature rise. Electrical limits interact with mechanics: higher speed increases back EMF, reducing available headroom for torque. Validate that stall current, locked-rotor conditions, and fault scenarios are contained by protections such as current limits, fuses, thermal sensors, and appropriate start or ramp profiles.

Sizing Workflow and Common Pitfalls

A disciplined workflow prevents surprises. First, define the motion profile and load: masses, radii, friction, and any vertical lift. Second, compute required torque across each segment, including acceleration with total inertia. Third, account for gearing, efficiency, and reflected inertia to the motor shaft. Fourth, calculate RMS torque and compare with continuous ratings; verify peak torque versus short-term ratings. Fifth, cross-check with the speed-torque curve of candidate motors and confirm drive current and voltage capability. Sixth, iterate with margins and thermal assumptions, and simulate the cycle if possible. Pitfalls include unit mistakes, underestimating friction, ignoring deceleration energy, overconstraining acceleration, and neglecting cooling. Watch for compliance and backlash in mechanisms that inflate overshoot and settling time. Before final selection, validate with a prototype or digital twin, measure true currents and temperatures, and refine the profile. Proper sizing yields a cooler, quieter, and more efficient motor system that endures the demands of real operation.